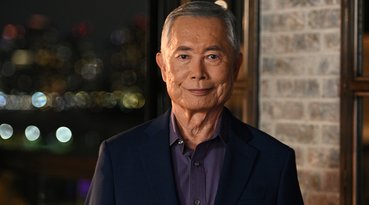

Jim Shepard isn’t obscure; he is—as he puts it—“semi-obscure. It doesn’t seem to me something I should be bitter about.” He acknowledges that few writers are truly famous—fiction and poetry is itself an increasingly obscure endeavor—but says that, “even among literary writers, it’s not like I’m a household name by any means.”

The nicer way of saying this is to call him a “writer’s writer” (he jokes that he has heard this term for much of his career). For years, Shepard has been one of those writers hanging at the periphery of literature, praised by his peers but not much known outside of literary circles; for example, think of George Saunders before Tenth of December and the New York Times encomium bounced him into superstardom.

Shepard has seemed to approach commercial breakthrough before—perhaps even with his sixth novel, 2004’s Project X, about a young sociopath who wreaks havoc upon a high school in ways psychological and physical. The real moment of breakthrough should have been his 2007 short story collection Like You’d Understand, Anyway, a series of first-person narratives that move from the Reign of Terror and Mother Russia, to the domestic space of a boy home sick from school, watching Jonathan Winters on TV. As an author, he often seems to disappear behind his research; without anything overtly “autobiographical,” how does a reader get to know Shepard? For Like You’d Understand, Anyway, Shepard was a National Book Award finalist—but as far as he’s concerned, this did little to move the needle on his fame: “[An interviewer] said, ‘How does it feel to be famous?’ I said, ‘Take this simple test: go on the street, tell the first 20 people you see that you’re interviewing me, and watch their faces.’ ”

The Book of Aron, his seventh novel, might be the book to change all this—for him to shirk off obscurity, semi- or otherwise. It’s a Holocaust novel in which a boy—narrator Aron—wanders through an increasingly depraved Poland, scamming and trading to survive, never quite aware of how his actions affect those around him. But where something like Anthony Doerr’s juggernaut All the Light We Cannot See is elegant and expansive, The Book of Aron is spastic and claustrophobic, concerned with the immediate experience of survival and more or less blind to history. “The dread of what’s coming is evoked in the reader’s mind,” Shepard says, “but it’s opaque to those who are there.” In other words, the reader understands the larger historical implications, whereas poor Aron only understands the filth of his living conditions.

So in a way, The Book of Aron is clearly a new Jim Shepard story, pinned to a narrow point of view, psychological and harrowing and detailed within an inch of its life. Of course, what makes his fiction work is that central paradox of literature: the more specific the story, the more universal its reach. “Literary fiction uses experiences you have had to conceive of experiences you haven’t had,” Shepard says—which means, if you’ve ever felt fear, you can understand Aron, even if you’ve never lived through such atrocity. “You feel as though you do have some sense of what it was like to go through those experiences. You don’t fool yourself into saying, ‘That’s the equivalent of being there,’ but you register that your conscious has been expanded in a way that seems authoritative.”

The narrowness of Aron’s point of view helped Shepard to find unusual ways into the novel; for example, when reading oral histories of children in Poland, “the amount of familial unhappiness that I confronted was startling to me. That felt like something I could really relate to.” The Book of Aron proves unique in this way. Its violence is very loud, yet equally loud is the family strife. Consider a “small” moment, like when Aron’s mom tells her husband, “If something happens to [Aron] I will never look at you again,” and her husband responds simply, “You never look at me now.” It seems minor, perhaps, but this brief exchange contains all the weight of a marriage under duress, and in its way, it’s as loud as any gunshot.

For Shepard, pa rt of the appeal of this book was the opportunity to embody “the limitation of a child’s voice, especially when confronting suffering. The idea of the child’s inherent helplessness seemed useful when confronting the Holocaust, which, in a way, makes children of us all.” Though Shepard pulls this off better than nearly anybody, it’s not a totally new notion, and one need not look very far into World War II-set novels (The Painted Bird, The Tin Drum) and films (Forbidden Games, Come and See) to find artists using children to confront horror. (And speaking of horror, isn’t this same notion at work in genre films like The Shining or The Exorcist—that innocence at the center makes everything more harrowing?)

rt of the appeal of this book was the opportunity to embody “the limitation of a child’s voice, especially when confronting suffering. The idea of the child’s inherent helplessness seemed useful when confronting the Holocaust, which, in a way, makes children of us all.” Though Shepard pulls this off better than nearly anybody, it’s not a totally new notion, and one need not look very far into World War II-set novels (The Painted Bird, The Tin Drum) and films (Forbidden Games, Come and See) to find artists using children to confront horror. (And speaking of horror, isn’t this same notion at work in genre films like The Shining or The Exorcist—that innocence at the center makes everything more harrowing?)

This raises another question for Shepard: how does he handle writing a story set during a time period that has been the backdrop for countless other narratives? With all the texts on the subject of World War II and the Holocaust, what traps can a writer fall into?

“We’ve gone from Adorno’s notion that no one can write about this,” Shepard says, “to it becoming its own genre with archetypes and motifs. Cynical readers wonder, ‘When will I see a shouting SS officer?’ On the other hand, some readers are disappointed when they don’t see that. There’s also the tension between sensationalizing and sanitizing. In a case like this, where there are unprecedented horrors, you remember it’s a problem that every fiction writer has—that you’re trying to defamiliarize the familiar and make familiar the outlandish.”

And there is much that’s familiar in The Book of Aron—and much that’s outlandish, sad, horrifying, and even, however improbably, funny. Does Shepard understand that this is his moment, or is The Book of Aron simply another project to him? Maybe I get a hint of an answer to this question when I ask him what details he just couldn’t squeeze into the book, and he reminds me about the lice, “the way [being covered in lice] would become the focus of your quotidian. I put a bit of that into the book, but I couldn’t render exactly what that was like or the bigger issues would get occluded.”

If this is his moment, then of course he needs to hit those bigger issues—he cannot obscure them or avoid them too much. But still, Jim Shepard being Jim Shepard, he needs to have his lice.

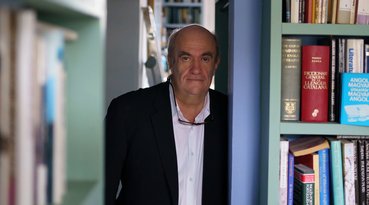

Benjamin Rybeck is events coordinator at Brazos Bookstore in Houston. His writing appears in Electric Literature's The Outlet, Ninth Letter, The Rumpus, The Seattle Review, The Texas Observer, and elsewhere, and has received honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Readingand The Pushcart Prize Anthology.