When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, George Takei was only 4 years old. The directive, which mandated the relocation of Japanese Americans to hostile landscapes all over the country, forced Takei and his family out of their cozy Los Angeles home and into a series of incarceration camps. Takei entered the camps at the age of 5 and would remain there until the conclusion of the war three years later, in 1945, when he and his family found themselves back in California, penniless and unhoused.

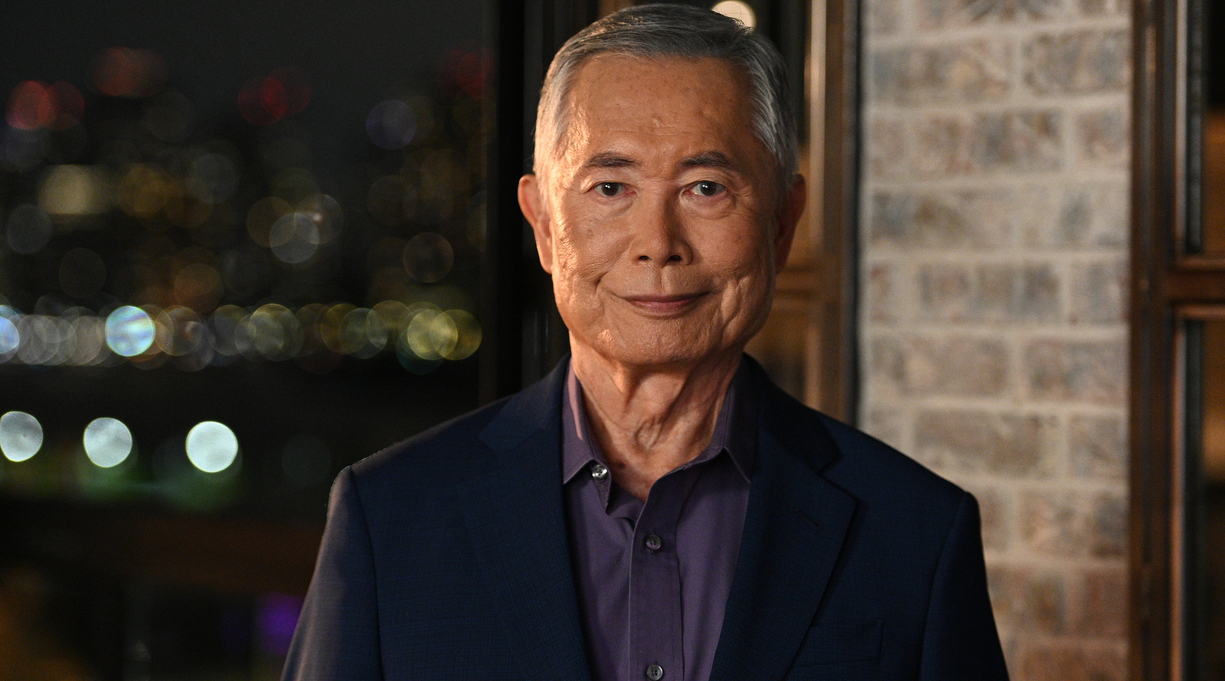

For decades, the actor and activist, beloved for his role as Lieutenant Sulu on Star Trek, has been vocal about this dark chapter in American history. In addition to speaking about his experiences in interviews and a well-received TED Talk, Takei received an Eisner Award for They Called Us Enemy, a graphic memoir for teens written with Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott and illustrated by Harmony Becker. His new picture book, My Lost Freedom: A Japanese American World War II Story (Crown, April 30), illustrated by Michelle Lee, is intended for a new audience: children and the adults who read to them.

I recently spoke to Takei, 87, over Zoom about picture books, multilingualism, democracy, family, and hope. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write this book?

This is my third visit to my childhood imprisonment. The first was my 1994 autobiography [To the Stars] and then in 2019 with my graphic memoir for teens.

Today, it’s particularly important for Americans to know how fragile our democracy is. We’re living through a presidential election year, and this fragility is vivid on so many different levels. And so, I thought, with my next visitation of the story, I will target two generations with one book: Daddy and Mommy reading to little Johnny and little Janey. Maybe the introduction of this history will pique the curiosity of daddies and mommies everywhere, so they’ll go and learn more. For the children, it’ll be their chance to learn about [the history of the camps] for the first time and maybe share it with their friends and classmates. I want my readers to feel prepared to deal with the complexities of American democracy.

Is that why this book works in a dual perspective? I noticed that young George, the child protagonist, often reveals his memory of a situation, which is quite positive, in contrast to his parents’ memory of the same situation, which is more realistic.

I lived through it all, but I didn’t understand it. Like when we were assigned a horse stall to stay in, my reaction was, “We get to sleep where the horsies sleep!” But I can still hear my mother mumbling, “So humiliating. So degrading.” The whole experience for my parents was torturous.

I lived through it all, but I didn’t understand it. Like when we were assigned a horse stall to stay in, my reaction was, “We get to sleep where the horsies sleep!” But I can still hear my mother mumbling, “So humiliating. So degrading.” The whole experience for my parents was torturous.

As a teenager, I became curious. I wanted to understand. As I recollect in the book, I had many after-dinner conversations with my father. He was a block manager at the camp, so he knew some of the things most of the people in the camp did not know, some of the problems and how they were resolved or not resolved. In those conversations, my father told me that he’d had such hope and ambitions for my brother and me. For him to see the barbed wire behind us tore him apart. What was our future going to be? What would our lives be like? Remembering that and writing about it, reliving those conversations, was painful. I sobbed at my computer.

Your parents seem extraordinary. I especially loved the scene when your mother sneaked a sewing machine into the camp. Can you tell us more about that?

Well, it was a sewing machine, so it was heavy. It was wrapped in baby blankets and sweaters in a duffel bag [with] lollipops, bubble gum, Cracker Jack boxes, and picture books for Daddy to read to us. For us, the fact that the bag was so heavy was wonderful—we thought it was going to be full of other goodies for us when we arrived at the camp! My mother marched past those soldiers with rifles, and I said to her, “Don’t let the soldiers take the candy away from us!” It was such a devastating disappointment when she revealed that all that weight was [actually] a sewing machine!

My mother was a gutsy and practical lady. She knew that her children were going to grow. They were going to need clothes. The reason my father was so shocked was that we could have gotten into real trouble. Anything with sharp edges or points was [considered] contraband. He was aghast, but he also realized his wife was his wife wherever they were.

Another thing I love about the book is the cover.

The back cover is actually my favorite illustration by Michelle Lee. It’s Camp Rohwer framed by dark, ominous swamp trees. I’d never seen a landscape like Arkansas with trees that loom up out of the black water, their roots coming out and going back in like a snake.

And the strange sounds that came from this jungle! (I call it the jungle, but it was really a forest.) I knew an older boy who said they were dinosaur sounds. I hadn’t heard of dinosaurs before. The boy said they were huge monsters, ugly, with fangs. He said they lived millions and millions of years ago, and then they died. And I said, “They died? Then how can we hear them out here?” He said, “Oh, they died all over the world except in Arkansas. They built those barbed wire fences to keep them caged in!”

What was life like after you were released?

After the camps, what saved us was that we lived in a minority neighborhood. We couldn’t go back to our old neighborhood. But the Mexican American community embraced us. They were friendly and welcoming. My mother made friends with our neighbor Mrs. Gonzales, and they taught each other their recipes. As far as I’m concerned, Mrs. Takei made the best enchiladas and tacos in East L.A.

In our new neighborhood, I heard Spanish all around me—I enjoyed the language! I then took Spanish classes all through junior high and high school. My minor in college was Latin American studies, where again, I maintained my Spanish. My major was theater arts, and my father said I had a hopeless major and a useless minor. He thought, I’m going to be supporting him all his life!

Despite everything that happened, you maintain an incredible sense of hope. Where does that come from?

It came from my father. He was [always] setting up dances for teenagers or building baseball diamonds or helping old folks. I really think my father was Superman to have done what he did in camp and still be our father.

I feel very blessed having the parents I had. We lived through so many scary, terrifying events [at the camp]. As long as we were with our parents, we were safe. My parents defined who I became—they and all the stresses we went through made me who I am today.

Mathangi Subramanian is a novelist, essayist, and founder of Moon Rabbit Writing Studio.