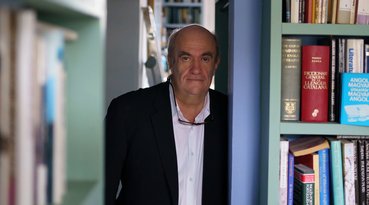

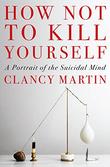

In his new book, How Not To Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind (Pantheon, March 28), Clancy Martin wastes no time getting to the dark heart of his subject. “The last time I tried to kill myself was in my basement with a dog leash,” he writes in the opening line of the preface. That tone—bluntly direct and deeply human—characterizes this remarkable volume, an attempt to bring discussion of suicide out of the shadows so that we can better understand the powerful impulse to kill oneself and how we might circumvent it.

A professor of philosophy at the University of Missouri in Kansas City and Ashoka University in New Delhi, as well as a novelist (How To Sell), Martin writes with disarming candor about his own suicide attempts—he counts more than 10—as well as his difficult childhood and struggles with alcohol. He also brings lenses both philosophical and literary to bear on the subject, invoking Plato, Nietzsche, Anne Sexton, and David Foster Wallace. Above all, he writes, he seeks to “sincerely and accurately convey what it’s like to want to kill yourself, sometimes on a daily basis, yet to go on living, and to show my own particular reasons for doing so.”

In a starred review, Kirkus calls How Not To Kill Yourself “disquieting, deeply felt, eye-opening, and revelatory.” It’s not an easy book to read, but it’s an urgently important one—especially for those contemplating suicide and their loved ones. We spoke with Martin, 55, by Zoom from his home in Kansas City; our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

This must have been a difficult book to write. How did it come about?

The impetus for the book was an article that I wrote for Epic magazine. An editor got in touch with me about writing a nonfiction piece. I said, “One thing I could write about is some time I’ve spent in psychiatric institutions. It could be a latter-day riff on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” We started working on it, and someone close to him attempted suicide. And he said to me, “I noticed as we’re working on this together that you tend to go to the psychiatric hospital because you tried to kill yourself. Well, that’s interesting. And I think you could help some people if you focused a little bit more on that.” So I did.

When the article came out, so many people emailed me from all over the world. This one kid sticks in my mind, a 16-year-old kid writing to me from England—incredibly bright, feeling the need to be very literary in the writing but also in such obvious pain—who said, “I was Googling how to kill myself, and I came across your article, and I didn’t kill myself.” Enough of that [sort of response], and you’re like, OK, I’ve finally done something worthwhile with my writing, and I need to do something more.

You write at length about your own struggle with alcoholism and how you came to see suicidal thinking as a form of addiction, too.

I remember this one young woman, from a stay in a psychiatric hospital, who had tried to kill herself more times than I had. She was a very magnetic person. If I think about it now, it was so clear that she was addicted to the thought of killing herself—this was just an addiction in a very traditional sense. If she had told me she was addicted to vomiting or to cigarettes or to Instagram, I would have immediately understood it. But it was right there in front of me that she was addicted to suicide, and I didn’t see it. And I never saw it until I wrote the book. The idea is at least as old as the Buddha—that one of our fundamental, habitual sources of suffering is a commitment to the idea of self-annihilation. The idea is right there waiting for someone to grab it.

You’re a professor of philosophy, and there’s obviously a connection between that field of inquiry and the issue of suicide. Could you say more about that?

Virtually every great philosopher—at least up until the 20th century, when things change a little bit—wrote about suicide. It just seemed reasonable to them, when thinking about what constitutes the question of the good life, also to think about what constitutes the question of a good death. You have a handful of great Christian philosophers who are writing against it for various reasons—some of them for social/political reasons, some of them for theological reasons. Once we get past the Enlightenment, they’re all writing in defense of the right to suicide because they see it as part of the emancipation of the life of the mind from the dogmatism of a particular Judeo-Christian worldview.

Virtually every great philosopher—at least up until the 20th century, when things change a little bit—wrote about suicide. It just seemed reasonable to them, when thinking about what constitutes the question of the good life, also to think about what constitutes the question of a good death. You have a handful of great Christian philosophers who are writing against it for various reasons—some of them for social/political reasons, some of them for theological reasons. Once we get past the Enlightenment, they’re all writing in defense of the right to suicide because they see it as part of the emancipation of the life of the mind from the dogmatism of a particular Judeo-Christian worldview.

I took an interest in the question of how many of the major and minor philosophers actually took their own lives, and it turns out that very, very few of them did. There’s a handful, but they really are in the minority compared with poets and writers and painters—even scientists and mathematicians. I believe that is due to the fact that if you take a good hard look at life—under ordinary human circumstances, up until maybe a certain age and a certain level of physical or mental deterioration—you will conclude that life is worth living. There might be very, very rough days, but those will come to an end and the sun will come out from behind the clouds again. I think a philosophical disposition, at the end of the day, actually leads one toward resisting the kinds of suicides typically associated with depression, despair, meaninglessness of life worries, all these kinds of things. Most of the great existential philosophers who considered this question seriously come to the same conclusion, that suffering is meaningful rather than meaningless.

What is your hope for the book?

My first hope is that people who are repeat suicide attempters will see the thing that I have started to see, that suicide is a bad idea. I might still want to do it, but at least I can see: Nope, that’s a bad idea. I hope that it will help some other people who have tried suicide, and failed, to shift their thinking so that they no longer see it as one good option that’s waiting out there for them.

My next hope is that it can contribute to a growing movement to help suicidal people generally, and particularly that it can become part of our national conversation about helping young people avoid making an attempt. The vast majority of the time suicide is not an impulsive act—it’s an expression of a pattern of thinking that’s been a long time in the making, and it’s going to take some real work on the part of that person and their loved ones to change that pattern of thinking, if we have the opportunity to do so.

The book has two appendices full of helpful resources—articles, books, websites, videos, podcasts, and interviews. Is there one you’d like to highlight for readers here?

One that I find to be particularly powerful is a series of portraits with people telling their stories that’s done by a suicidologist named Dese’Rae L. Stage. The website is Live ThroughThis.org, and it’s very, very effective. There’s also the Trevor Project for LGBTQ+ kids (thetrevorproject.org) that is incredibly important for the most vulnerable population right now. Those are two that I think are particularly good and undermentioned.

Tom Beer is the editor-in-chief.