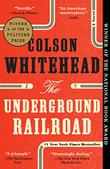

Colson Whitehead’s 2016 novel, The Underground Railroad, won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, and the Arthur C. Clarke Award. It was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize and was a finalist for the Kirkus Prize. Indeed, it may be the most acclaimed alternate-history novel of all time, but it’s very different from other books of its genre.

Many alternate-history tales hinge on massive changes in the timeline. In Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, for instance, the Axis powers win World War II; in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, an antisemite is elected president, defeating Franklin D. Roosevelt. But Whitehead’s novel, which takes place in the early 1800s, takes a different tack; in its version of history, there are significant changes, including marvels of engineering that are many years ahead of their time—an interstate, subterranean transit system; skyscrapers in South Carolina—and some alterations in the way some state governments are run. But these changes aren’t harbingers of a new evil; instead, slavery, the greatest evil of the era, remains firmly in place. It’s a new version of history, but one that harmonizes with the old version. A new Amazon Prime Video miniseries adaptation, directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Barry Jenkins, gets across the novel’s detailed vision with sumptuous visuals and simmering intensity.

In a 2016 interview with Kirkus Reviews, Whitehead remembered when, in the year 2000, he came up with the notion that literalized the title of his novel: “What if the Underground Railroad were a literal system of tracks? It’s oddball and impossible, but it seemed too strange to pass up.” In the book, an enslaved woman, Cora, escapes a Georgia plantation with an enslaved man, Caesar, and takes this subterranean train to South Carolina. There, the pair live under assumed names and far better conditions, but they’re not entirely free; the United States government still claims ownership of them. Cora is given a job as an actor in a “Living History” exhibit called “Typical Day on the Plantation,” where spectators gawk at her.

A horrible secret about their new home forces Cora to separate from Caesar and take the underground railroad to North Carolina, a state in which no Black people, enslaved or free, are allowed, and where she’s forced to hide in an attic. A man named Ridgeway, who is hired to hunt her down, eventually captures her and attempts to bring her and another man back to Georgia through Tennessee. Cora later ends up in Indiana, as part of a community on a farm owned by a free Black man; there, she begins a tentative romance with a man named Royal. But Ridgeway hasn’t given up his pursuit, and tragedy continues to befall Cora and those around her.

The miniseries changes surprisingly little in its translation to the small screen, and what minor alterations there are only enrich the experience and often deepen the characterizations. One of the greatest differences between novels and films is the fact that, in a book, everything must be accomplished with the written word. Movies and TV shows, by contrast, can silently gaze upon a landscape or an object; they can use a swell of music on a soundtrack to conjure a mood, or linger on an actor’s expression to convey an emotion. It’s an unfiltered experience that words on a page simply can’t achieve in the same way, and Jenkins revels in these moments here—the surreal tableau of the South Carolina museum; a mural in an underground railroad station; two figures falling, in slow motion, off a ladder.

The miniseries changes surprisingly little in its translation to the small screen, and what minor alterations there are only enrich the experience and often deepen the characterizations. One of the greatest differences between novels and films is the fact that, in a book, everything must be accomplished with the written word. Movies and TV shows, by contrast, can silently gaze upon a landscape or an object; they can use a swell of music on a soundtrack to conjure a mood, or linger on an actor’s expression to convey an emotion. It’s an unfiltered experience that words on a page simply can’t achieve in the same way, and Jenkins revels in these moments here—the surreal tableau of the South Carolina museum; a mural in an underground railroad station; two figures falling, in slow motion, off a ladder.

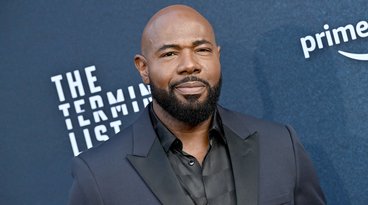

There’s one particular scene, in which a fire spreads through a town, that’s new to the adaptation, and Jenkins’ breathtaking visual style makes it indelible. This won’t come as surprise to many viewers; the director’s Oscar-winning 2016 film, Moonlight, and his 2018 adaptation of James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk were just as visually arresting. As in those films, his cast does wonderful work here: South African actor Thuso Mbedu, who plays Cora, is relatively unknown in the United States, but her bold, multifaceted performance will remedy that; Joel Edgerton brings an obsessive edge to the role of the unrelenting Ridgeway; and The Good Place’s William Jackson Harper plays Royal with a bright openness that’s surprisingly affecting.

There’s also an additional character in the miniseries, sensitively played by Mychal-Bella Bowman, who doesn’t exist in the book. She’s a minor player, to be sure, but Jenkins devotes an entire episode to her—one that offers an unexpected note of hope. It’s a note that doesn’t appear often in Whitehead’s symphony, but it doesn’t feel dissonant here; it’s an alternate version of the story, but one that’s fully in harmony with the original.

David Rapp is the senior Indie editor.