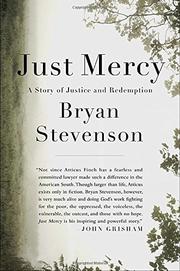

JUST MERCY

by Bryan Stevenson

A distinguished NYU law professor and MacArthur grant recipient offers the compelling story of the legal practice he founded to protect the rights of people on the margins of American society.

Stevenson began law school at Harvard knowing only that the life path he would follow would have something to do with [improving] the lives of the poor.” An internship at the Atlanta-based Southern Prisoners Defense Committee in 1983 not only put him into contact with death row prisoners, but also defined his professional trajectory. In 1989, the author opened a nonprofit legal center, the Equal Justice Initiative, in Alabama, a state with some of the harshest, most rigid capital punishment laws in the country. Underfunded and chronically overloaded by requests for help, his organization worked tirelessly on behalf of men, women and children who, for reasons of race, mental illness, lack of money and/or family support, had been victimized by the American justice system. One of Stevenson’s first and most significant cases involved a black man named Walter McMillian. Wrongly accused of the murder of a white woman, McMillian found himself on death row before a sentence had even been determined. Though EJI secured his release six years later, McMillian “received no money, no assistance [and] no counseling” for the imprisonment that would eventually contribute to a tragic personal decline. In the meantime, Stevenson would also experience his own personal crisis. “You can’t effectively fight abusive power, poverty, inequality, illness, oppression, or injustice and not be broken by it,” he writes. Yet he would emerge from despair, believing that it was only by acknowledging brokenness that individuals could begin to understand the importance of tempering imperfect justice with mercy and compassion.

Emotionally profound, necessary reading.